MAZURIANS – WHO WERE THEY? WHO ARE THEY?

Mazurians – who were they? Who are they?

Who exactly are the Mazurians?

Are they just people living in Masuria?

Is it possible to call anyone who lives in the Land of a Thousand Lakes?

Maybe let’s start from the beginning, so a bit of history.

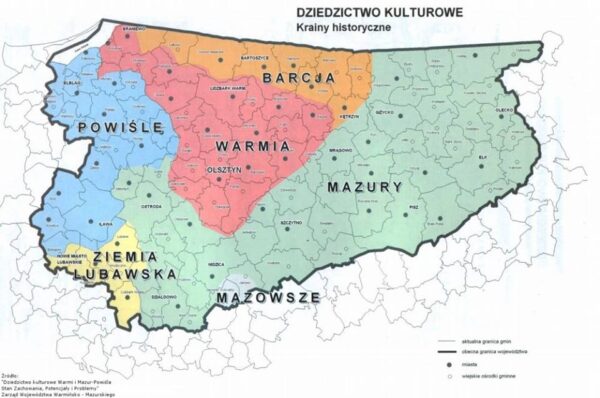

The pagan tribes of Prussia lived here, conquered in the 13th century by the Teutonic Knights. The pagan tribe of Warmia lived in Warmia, after which this land took its name, which the Pope then gave under the authority of the bishops. On the conquered lands of Prussia, the Teutonic Knights built their monastic state. There, colonists coming from Mazovia began to establish their settlements. The area where they founded their villages was later called Masuria.

It is worth mentioning that the very name of Masuria was popular only in the 19th century!

It can be said that Masurians are immigrants who, from the turn of the 15th and 16th centuries, migrated (or escaped) to the territories of the Teutonic State from overpopulated northern Mazovia. Masurians, going from the south, reached the Great Masurian Lakes, where they founded their villages, then some turned into cities, where they spoke their language – then Polish. Masurians cultivated regional rituals and customs. They formed relatively closed communities with a typically agricultural culture separate from the culture of German colonists, Prussian inhabitants or Lithuanian-speaking neighbours.

If you want to see what the Masurians looked like, get to know their customs and everyday life and look at Masuria from the observation towers, it is worth going to the places from the list below:

The Museum of the Polish Reformation in Mikołajki – here you will find out that the real Masuria is an Evangelical one;

Marcinkowo – Regional Chamber: here you will see how the Masurians dressed and what equipment were used on a daily basis

Mikołajki, Mrągowo, Giżycko: here you will see Evangelical churches, and if you ask pastors, you will learn something about the history and everyday life of Evangelicals

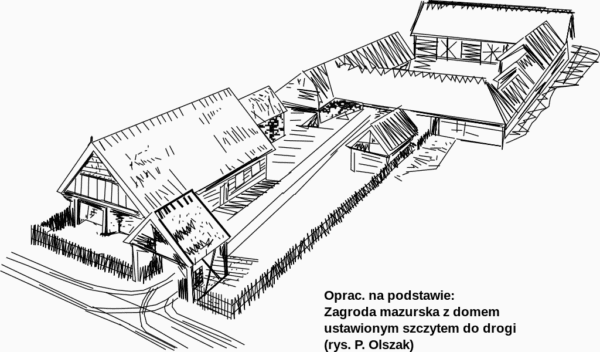

Kadzidłowo – Cultural Settlement: here you will see where and how the Masurians lived

Muławki – The 19th century manor house: a historic manor house that was situated in the Masurian landscape

Bezławki – church (former Teutonic castle): the church does not function and is closed every day, but with a bit of luck, you can climb the 18th-century tower, from which there is an amazing view of the Masurian landscapes;

Gierloz – Hitler’s headquarters: here you will see the sad consequences, the continuation of the history of Masurian land and learn about the backstage of the attack on Hitler on July 20, 1944.

Mamerki – the headquarters of the Reich army: here you will also see bunkers in the quarters that survived World War II, historical plaques and the reconstruction of the Amber Room, and you will enter a high, metal observation tower with a great view of Masuria

After the defeat of World War I by Germany, the victorious countries agreed that in some areas of the present Republic of Poland (including Silesia and Masuria), plebiscites (votes) would be held about the country in which the current inhabitants wanted to live. In Masuria, 99% of voters in the 1920 plebiscite wanted Masuria to stay in Germany (formally: in East Prussia). Poland, which returned to the maps of Europe after more than 120 years, was for them a new, unknown and less attractive state than the Prussian state where their ancestors lived for 300 years.

Meanwhile, the myth that Masurians really wanted to belong to Poland has become established in Polish literature, but the Germans made it impossible for them by intimidating their citizens. The truth, as always, turned out to be much more complicated. Even though the Germans, even under the threat of corporal punishment, persuaded the people to vote in favor of remaining in their country, only a dozen or so percent would vote for incorporation into the Polish state.

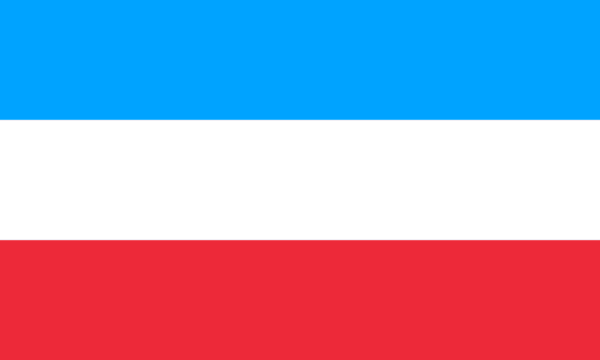

Only after the Germans lost the war, Masuria was incorporated into Poland in 1945Masurians were a typically agricultural community, deprived of a layer of urban intelligentsia. Although they did not develop a strong representation, there were people who studied at the University of Königsberg. Masurian youth undertook activities there to integrate the Masurian community, perpetuating Masurian culture, history and customs. This is how the design of the Masurian flag was born, which symbolizes the Masurian community to this day. Its three colors: blue, white and red refer to the colors of the Masovia Student Corporation, which was founded in 1830 by Masovian students at the University of Königsberg (the former capital of Prussia, today Kaliningrad). They borrowed the colors from the colors of the French Revolution, which symbolized:

fidelity – blue

honour – whiteness

love of law and truth – red

Each region, apart from the dialect, customs and religion, also has its own traditional folk costume.

The people of Masuria were not rich, therefore the costumes were simple, austere and did not have too many decorations. Weaving was a very well developed field of home production in the Masuria region. Women’s and men’s clothing differed depending on the season, property status, and the circumstances in which the garment was worn. The Masurian outfit was in common use in the years 1820-1870. They were sewn from homespun fabrics in dark and subdued colors, with stripes or checks. Fragments of such fabrics have been preserved. The women did not wear an apron with their festive attire. They wore a black velvet or white linen cap over their heads, and the caftan and skirt were usually of the same material. Amber necklaces were worn.

Who can be called Mazur today? After all, we are in the 21st century, people whose ancestors came here after the war live in Masuria, and their graves are here. And yet, even intuitively, we feel that Masuria, who were citizens of the German state before the war, differ from Masuria, who call themselves that because of their current residence and origin from post-war settlers.

A new generation of people who were born here lives and builds a new Masuria in Masuria. They say that they are Masuria because they grew up in Masuria. Here is their world, their home, here are their roots. It is worth knowing, however, that it is a group differently, historically or mentally than the descendants of the Masurians who lived here before the war, whose ancestors had lived in Masuria for hundreds of years. These are no longer people who use the Masurian dialect or are Evangelicals.